At Kintegra Health, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) serving several counties west of Charlotte, care coordination is increasing access to oral health services. Today, Kintegra’s 11 dental navigators are helping families understand their oral health needs, recording an astonishing 70 percent treatment completion rate.

In a recent blog post, Parker Norman shared how dental care management workforce models use care coordination to help providers address social determinants of health and expand access to oral health care services. In this post, she explores two examples in North Carolina.

What is Care Coordination? A Quick Review

As a recap, through care coordination, patients are connected with the resources they need to access oral health care services, including reliable transportation, comprehensive oral health insurance coverage, providers who accept that insurance, and providers who speak the same language as their patients.

Communicating with patients in their native language is especially important.

By speaking the same language as the people in the communities they serve, care coordinators can often help patients feel more comfortable. Coordinators — often referred to as “navigators” — can also promote oral health literacy through patient education delivered in a patient’s native language. With an understanding of the importance of good oral health, people are more likely to seek and utilize oral health care services.

Dental Care Management Models

Dental care management models include dental navigator models and the ADA-formalized Community Dental Health Coordinator model (CDHC). Both models aim to employ culturally competent individuals from the communities they serve. These coordinators are better able to understand vulnerable patient needs and connect them with the resources necessary to access optimal oral health.

Dental navigator models and the CDHC model are already used in North Carolina, and both are expanding access to care. Dr. William (Bill) Donigan, dental director at Kintegra Health, and Crystal Adams, a registered dental hygienist and director of Catawba Valley Community College’s (CVCC) dental hygiene program, provide insight about these models and offer recommendations for North Carolina as more are put into practice.

Care Coordination Case Study: The Dental Navigator Model at Kintegra Health

Kintegra Health first began to use the dental navigator model in 2006 as part of a school-based program, with hygienists calling parents to schedule their children’s appointments. By 2010, dental navigators joined the hygienists at schools to help schedule appointments. Starting in 2012, Kintegra hired a dental navigator for every county served by its school-based program —one navigator each in Davidson, Lincoln, Catawba, and Iredell Counties, and two in Gaston County.

By 2016, Kintegra Health was placing dental navigators in other health care areas, including pediatric medical, OBGYN, and Women Infant Children (WIC) clinics. These navigators provide patient and parent education, schedule appointments in communication with parents, and apply fluoride varnish for children. Although this program primarily serves children, some adultOBGYN patients are also served. There is limited space for adults in Kintegra’s dental clinics, so teledentistry is often used during medical appointments to bridge this gap.

At Kintegra Family Health in Statesville, the pediatric medical clinic and family dentistry clinic once shared a waiting room. Since the offices were side-by-side, it was assumed that a medical provider would give a dental referral to patients and their parents, who would then schedule the appointment. Because of this, no dental navigator was employed at that location.

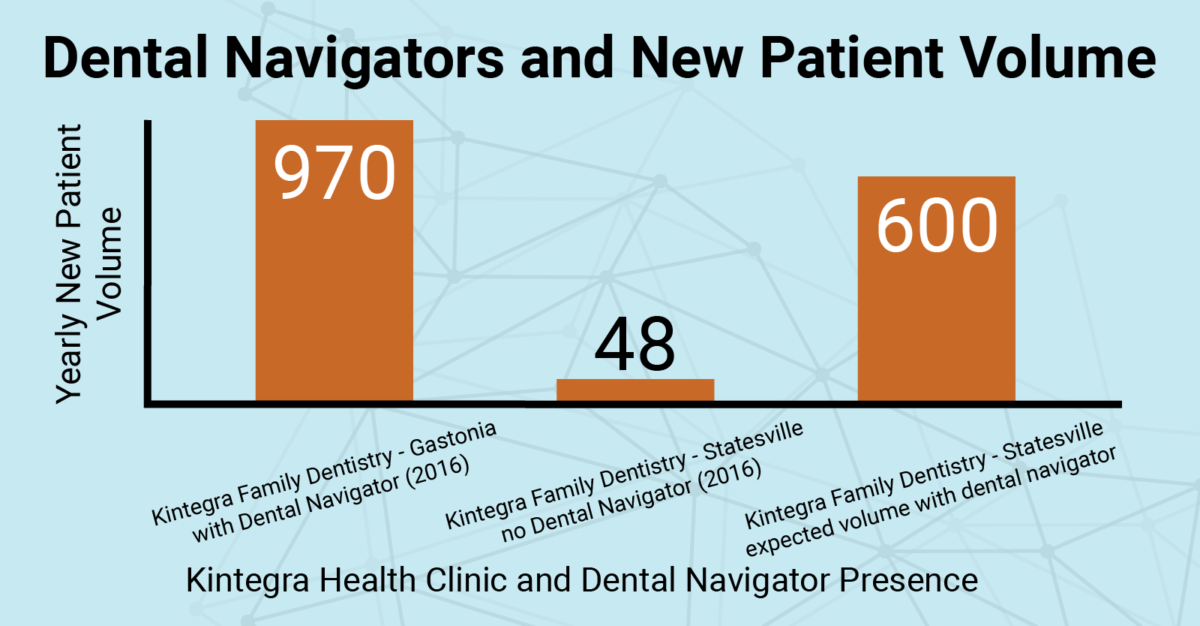

In 2016, almost 970 new patients saw a dentist at Kintegra Health in Gaston County, where a dental navigator was employed in the pediatric medical clinic. During the same year, only 48 new dental patients were seen at Kintegra’s Statesville location. Howeer, after a navigator began working in the Statesville WIC clinic, more than 50 new patients saw a dentist in just one month. The figure below compares expected patient volumes during one year with dental navigators and one year without.

Kintegra Health has measured a 70 percent treatment completion rate for patients receiving oral health care with the help of dental navigators, compared to about a 30 percent completion rate in private practice.

With statistics like that, it is clear to see that Kintegra Health’s dental navigator model is increasing access through care coordination. There are now a total of 11 navigators employed by Kintegra Health and, during the last eight years, these navigators have helped more than 9,500 patients access dental care.

If Dr. Donigan were to start a new clinic, he said he would first employ a CDHC, rather than a dental navigator. A CDHC is trained to present the program to key stakeholders, some of whom are outside of the clinic setting, such as at school board meetings. CDHCs are also trained to use motivational interviewing techniques to expand the program.

After patient volume began to increase, Dr. Donigan would then start employing dental navigators to speak one-one-one with parents and patients. As he already does at “Dr. Donigan’s School of Dental Navigation,” he would train the new dental navigators on-site in oral health education. He would also require that they complete the Smiles for Life program, which equips primary care providers to promote oral health for all age groups, and he would require that they become Dental Assistant IIs (DA2).

Catawba Valley Community College CDHC Program

Catawba Valley Community College’s CDHC program is a year-long program with specific curriculum, training, and internship requirements. Before entering the program, a CDHC candidate must also have a professional DA2, Child Development Associate, or Registered Dental Hygienist license. It often takes longer for a CDHC to be able to find employment, compared to a dental navigator, given the formalized criteria that must first be met. However, once employed, a CDHC is already equipped with education and training.

In North Carolina, there are no CDHC-title jobs available — most jobs are marketed as general dental navigators without a specific CDHC requirement. Because of this, most students in CVCC’s program complete it as part of their continuing education and go on to work in other oral health roles. The positive outcomes of the program need to be proven to stakeholders so that CDHC jobs are actually funded before CDHCs will be employed as CDHCs.

“Let’s not look at the dollar, let’s look at the people,” Adams said, referring to the important work CDHCs could do to help people navigate barriers and access oral health care.

Adams also mentioned that while the CDHC curriculum is nationally formalized, care coordination is not “cookie cutter,” and there is no one-size-fits-all model. Different dental offices serving different populations will go about care coordination differently. At CVCC, Adams is adapting the program to make sure it is up-to-date and applicable for target populations in North Carolina. This includes educating students on things that may vary across state borders, such as insurance coverage.

CVCC will enroll its third cohort of CDHC students this January.

Dental navigator and CDHC models in North Carolina expand access to oral health care for vulnerable populations, addressing oral health inequities and improving overall oral health outcomes. The positive consequences and areas for improvement for both models should be considered as we move forward to implement future models effectively.

Over the 2020-2021 academic year, Parker Norman will be conducting a formative process evaluation of the CDHC program at CVCC. The evaluation will confirm if the program is feasible, appropriate, and acceptable, as well as inform decision-making related to the program’s improvement and ensure long-term success. Be on the lookout for the outcomes of this research, which will be applicable to other current and future programs!