The Next Generation Dental Office is Here

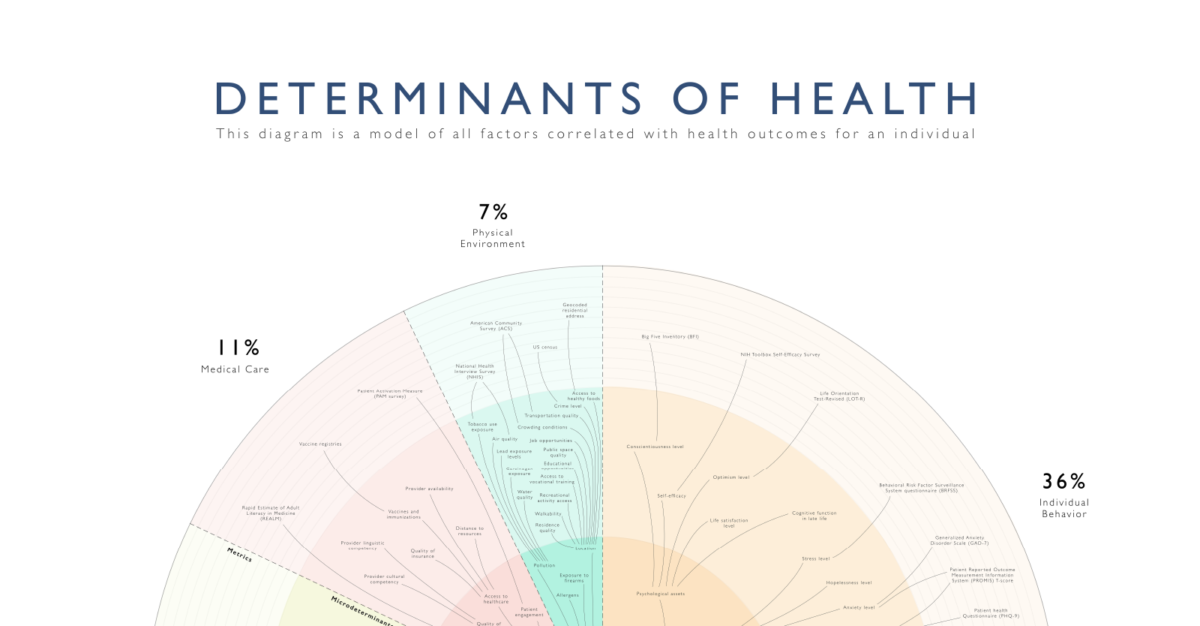

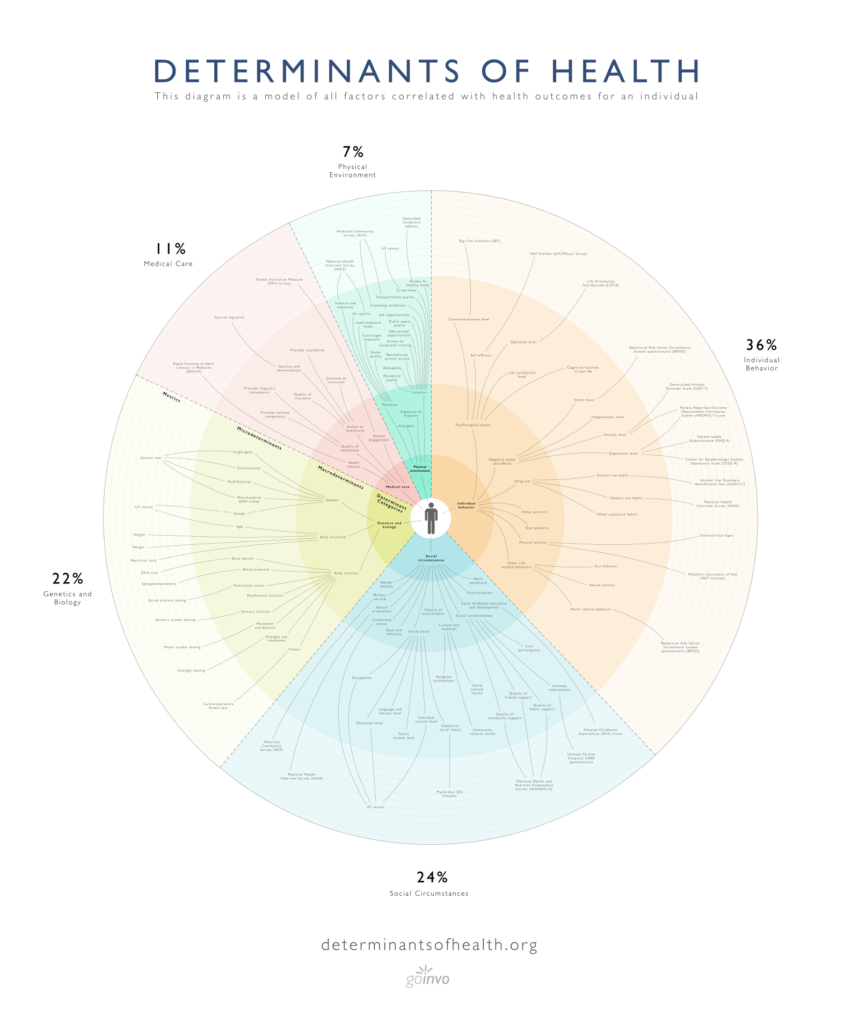

In the 21st century, modern dental practices have evolved to further place the overall health and well-being of the patient at the center through interprofessional collaboration and integration. Most notably, many dental practices now monitor blood pressure, screen for glycemic control, and educate patients on the connection between oral health and chronic diseases such as diabetes, osteoporosis and heart disease.

Will you get your next flu shot at the dentist, too?

In this blog post, we’ll examine the opportunity for dental professionals to improve and protect public health by administering vaccines, particularly for HPV and seasonal influenza.

Vaccinations in the United States: A Brief Background

Vaccinations are a core component in the fight against disease, helping build immunity prior to infection. Today, vaccines are available to help protect against diseases such as tetanus, Hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella, and whooping cough, just to name a few. In recent years, effective vaccination even eliminated smallpox.

A list of vaccine schedules outlining what vaccines are recommended at which ages can be found here.

Despite their effectiveness, millions of U.S. residents forgo vaccination each year. Fueled by scientific skepticism, distrust, cost, lack of insurance coverage, and other factors, vaccination rates in the United States are declining. A 2019 study found that between 2009 and 2018, 27 U.S. states reported a drop in the percentage of vaccinated kindergarten-age children.

According to the study, “For diseases with deadly potential … vaccination rates have fallen or remained below ideal thresholds.”

Despite this unfortunate reality, significant opportunities exist to improve and protect public health through vaccination, and oral health professionals can and should be part of the solution.

Dentists and Vaccination

You might be surprised to learn that dentists administer injections far more often than their medical counterparts. Each year millions of patients visit the dentist without visiting a medical provider. According to information from the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ), in 2017 alone, more than 31.1 million people in the U.S. sought care from a dentist, but not from their physician. According to the American Dental Association (ADA), “approximately 9 percent of Americans see a dentist, but not a physician, annually.”

Because dentists are skilled at administering injections, and they routinely engage with patients who do not frequently visit medical providers, dental visits are a prime opportunity for vaccination.

There is historical precedent for dentists and dental professionals delivering vaccinations as well. During the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, dentists in certain states were permitted to administer vaccinations to help fight on the frontlines of the pandemic response.

In 2019, the Oregon state legislature approved a bill allowing dentists to prescribe and administer vaccines. The law is expected to go into effect later in 2020. Other states that allow dentists to administer vaccinations include Minnesota and Illinois, which permit dentists to deliver the flu vaccine.

Allowing dentists to administer vaccines could have particular significance as the nation prepares to optimize delivery of an anticipated Coronavirus vaccine. According to the American Association of Dental Boards (AADB), at least one half of U.S. states have considered allowing the administration of COVID-19 vaccines by dentists once they become available.

HPV Vaccine and Reducing Oropharyngeal Cancer Risk

Even with scope of practice modifications, the dental office will likely never become a major access point for certain common vaccinations, like those for tetanus and Hepatitis B. However, there is a significant opportunity for oral health professionals to play a key role in providing vaccines for diseases with strong connections to oral health, as well as seasonal vaccinations.

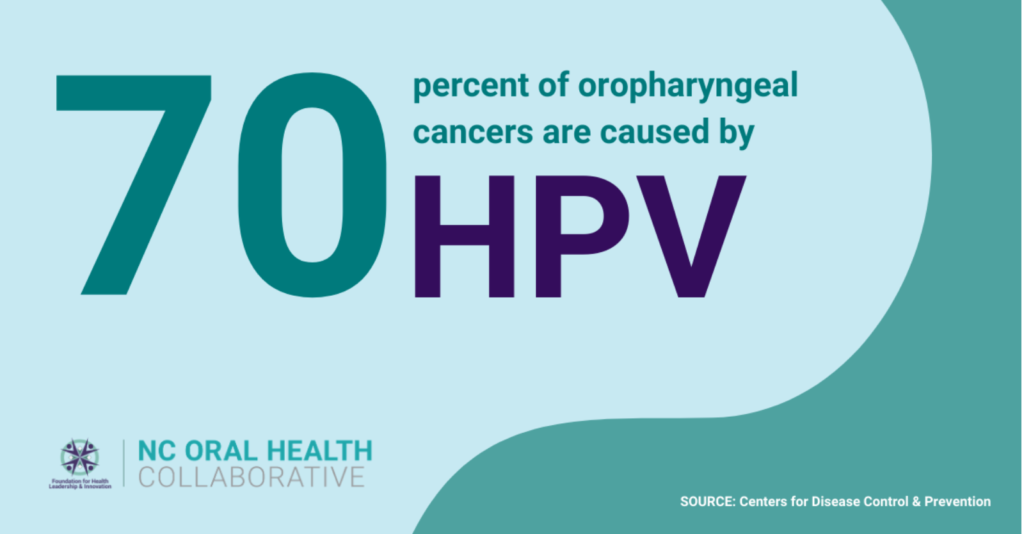

The human papillomavirus (HPV), for example, is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, and it significantly raises the risk of oropharyngeal cancer. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), HPV causes an estimated 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancers.

HPV’s connection to oral health means that dental professionals are prime candidates for delivering HPV vaccinations, monitoring vaccine compliance, and providing patient education. Allowing dental professionals to provide these services would increase efficiency and vaccination rates while lowering costs.

Routine vaccinations, including the seasonal flu vaccine and anticipated coronavirus vaccine (which is likely to be required annually), could also be effectively administered by dental professionals, achieving the same objectives.

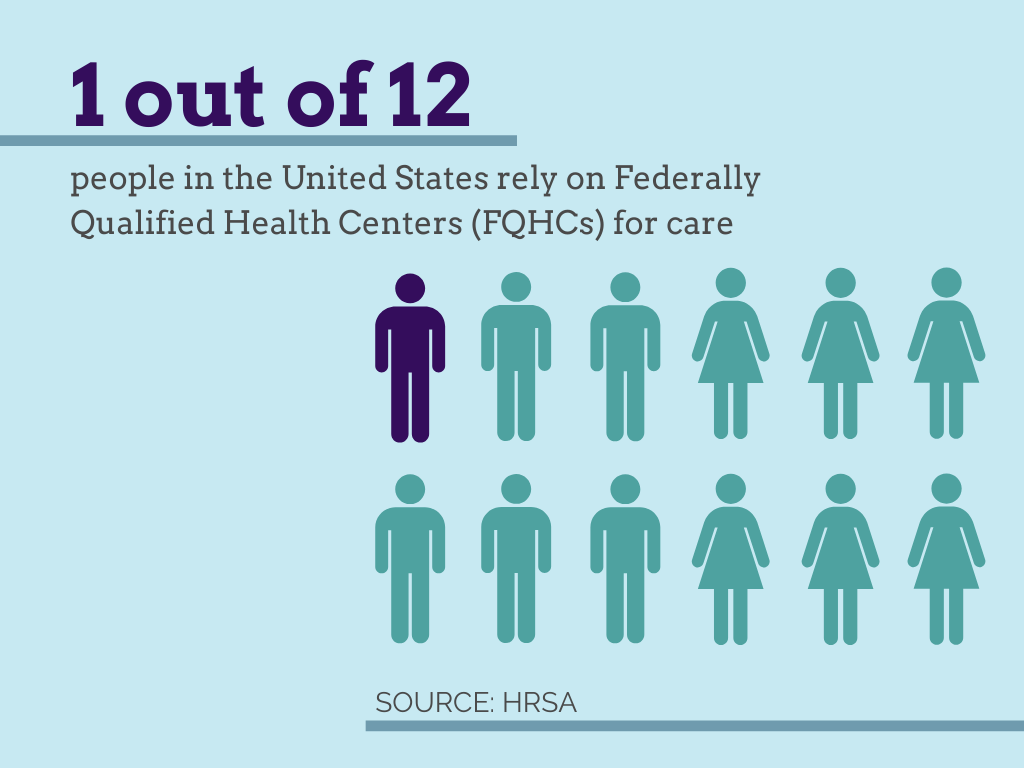

Federally-Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), in particular, are excellent sites for providing these vaccines, as dental-medical care is often integrated in pursuit of whole-person health.

Challenges to Dental Professional-Administered Vaccines

This not to say there are not challenges for this model of dental professional-administered vaccination.

Perhaps most significantly, throughout modern history, dentistry has been seen as separate from medicine. Rather than being viewed as an integral part of whole-person health, oral health has been siloed, effectively undermining opportunities to promote vaccination. Unfortunately, there will always be those who push back against further dental-medical integration.

Other, more practical, obstacles also present challenges to dental vaccine programs. In a recent op-ed published by the ADA, Dr. Joseph Kwan-Ho Yun outlines several of these, including a lack of training, a lack of adequate medical history, and payment and billing practices.

These challenges are certainly not insurmountable, and Kwan-Ho Yun acknowledges the benefits of such programs.

“Dentists may find it beneficial to focus on seasonal and targeted interventions such as the flu and HPV vaccines,” said Kwan-Ho Yun.

Regardless of how dental vaccine programs evolve, it is also apparent that dental-medical integration is both a prerequisite and an outcome. “This policy furthers integration of dentistry and medicine,” said Kwan-Ho Yun.

Outlook for Dental Vaccine Programs

Will your next vaccine be administered by a dentist?

Scope of practice expansions are under consideration in multiple states, and it is clear that dental professionals have the experience and expertise to play an important role on the frontlines of improving and protecting public health through vaccination, especially for HPV and seasonal diseases like influenza.

The coronavirus pandemic, in particular, presents a unique opportunity and may prove to be the impetus for driving policy changes necessary to expand dental vaccine programs nationwide.

Let’s hope so.

“Dental professional-administered vaccines, especially for oral health-related diseases like HPV, can have a tremendously positive impact on increasing vaccination rates, improving population health, and encouraging dental-medical integration,” said Dr. Zach Brian, NCOHC director. “It will be prudent that oral health stakeholders further explore this opportunity, and collaboratively enact policy to accomplish it.”

Dentists in North Carolina are not currently allowed to administer vaccines, however the North Carolina Oral Health Collaborative (NCOHC) is actively engaging in conversations with policymakers, legislators, and advocates to explore opportunities.

To join the effort to improve access and equity in oral health care in North Carolina, sign up to become a member today. Membership is free and by joining you’ll get instant access to our exclusive resources, events and updates for oral health advocates.